Rapa Nui, known as Easter Island, did not experience a catastrophic population collapse as previously believed, according to new analysis of ancient DNA from 15 former inhabitants. The study, published in Nature, found no evidence of a genetic bottleneck, suggesting the island's population steadily grew until the 1860s when slave raiders from Peru forcibly removed a significant portion of its people.

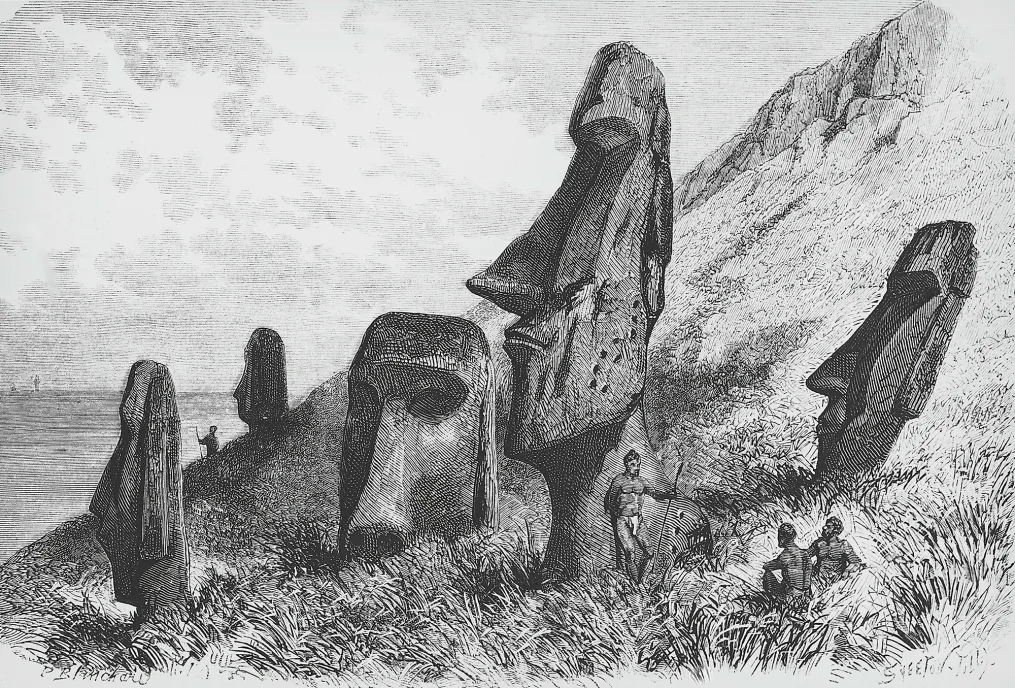

Researchers sequenced the genomes of individuals who lived on the island over the past 400 years, revealing that the Easter Islanders had exchanged genes with Native Americans between 1250 and 1430, long before Columbus reached the Americas. This suggests the inhabitants crossed the ocean to South America centuries ahead of European contact. Rapa Nui is today a part of Chile and has long been a source of a fascination. An engraving depicts the giant statues, or moai, at the volcanic crater Rano Raraku. J. L. Charmet/De Agostini/Getty Images

Rapa Nui is today a part of Chile and has long been a source of a fascination. An engraving depicts the giant statues, or moai, at the volcanic crater Rano Raraku. J. L. Charmet/De Agostini/Getty Images

Contrary to theories like those presented by Jared Diamond in his book "Collapse," which portrayed Easter Island as an example of ecological self-destruction, the DNA evidence indicates a sustainable society. Experts, such as Lisa Matisoo-Smith, argue that the narrative of a self-inflicted collapse is false, highlighting the remarkable navigational skills of Polynesian seafarers who discovered Rapa Nui 800 years ago and likely reached South America well before European explorers.